Utopian Socialism

Utopian Socialism

Links to the writings and biographies of Utopians

and Marxist commentaries on them, and material on 20th century utopian

movements and the use of utopian and dystopian visions in literature and

political polemics.

Utopia – literally “nowheresville” – was the name of an imaginary

republic described by Thomas More in which all social conflict and

distress has been overcome. There have been many versions of Utopia over

the years, many of them visions of socialist society. Although Marx and

Engels defined their own socialism in opposition to Utopian

Socialism (which had many advocates in the early nineteenth century),

they had immense respect for the great Utopian socialists like Charles

Fourier and Robert Owen.

By describing how people would live if everyone adhered to the

socialist ethic, utopian socialism does three things: it inspires the

oppressed to struggle and sacrifice for a better life, it gives a clear

meaning to the aim of socialism, and it demonstrates how socialism is ethical, that is, that the precepts of socialism can be applied without excluding or exploiting anyone.

The problem with Utopian socialism is that it does not concern itself with how to get there, presuming that the power of its own vision is sufficient, or with who the agent of the struggle for socialism may be, and, instead of deriving its ideal from criticism

of existing conditions, it plucks its vision readymade from the

creator’s own mind. Over 40 versions of Utopia were published between

1700 and 1850. Engels makes special mention of Morelly’s Code of Nature

See also Utopia in the Encyclopedia of Marxism.

Early Utopian Imaginings

Plato (428-347 BCE) wrote The Republic

in 360 BCE, an idealisation of a slave society with a rigid class

system, divided between philosophers, warriors and commoners. Justice

and social stability were ensured because everyone was assigned to a

station in life appropriate to their interests and virtues. The

structure of the Republic was an image of Plato’s conception of the

structure of the human being: Reason, Spirit and Desire.

Full text of The Republic from M.I.T. (360 BCE)

Thomas More wrote Utopia

in 1515, looking forward to a world of individual freedom and equality

governed by Reason, at a time when such a vision was almost

inconceivable.

“in Utopia, where every man has a right to everything, they all know

that if care is taken to keep the public stores full, no private man can

want anything; for among them there is no unequal distribution, so that

no man is poor, none in necessity, and though no man has anything, yet

they are all rich; for what can make a man so rich as to lead a serene

and cheerful life, free from anxieties;”

Full text of Thomas More’s Utopia (1515)

See Thomas More and his Utopia, Karl Kautsky 1927

Forward to Thomas More‘s Utopia William Morris 1893.

Forward to Thomas More‘s Utopia William Morris 1893.

With the Reformation in Germany and numerous independent republics

enjoying freedom in Northern Italy, modern, egalitarian ideas were

spreading, and a number of Utopian ideas were published in the sixteenth

century: – Antonio Doni’s humanist I mondi (1552), Francesco Patrizi’s La città felice (1553) and Tommaso Campanella’s La città del sole (1602)

Francis Bacon’s scientific New Atlantis

(1627) tells of a “lost civilisation” that lives in perfect harmony and

peace. Their society is dedicated to the accumulation of knowledge and

the study of science and nature, their division of labour being akin to

that of a modern research institute, a social embodiment of the ideal of

Reason.

Full text of Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1626)

Every Utopia is in fact an expression, in the language of social institutions, of the creator’s own conception of Reason.

A number of Christian writers expressed their vision of the Christian

ethos in opposition to the Church of their time in the form of Christian

Utopias. These include Antangil of “I.D.M.” (1616), Christianopolis of Johann Valentin Andrae (1619), and the Novae Solymae libri sex of Samuel Gott (1648).

The Digger, Gerrard Winstanley outlined in detail an egalitarian utopia in which

a Parliament elected by universal suffrage decides the law, and the law is enforced by unpaid officers of the state; everyone must work and egalitarianism is strictly enforced.

Full text of Gerrard Winstanley’s The Law of Freedom (1652)

James Harrington’s Common-Wealth of Oceana

(1656) was based on universal land-ownership and was a militant

republic dedicated to spreading its democratic system to the rest of the

world. Harrington’s well-meaning vision almost landed him in prison and

Cromwell banned it.

Full text of James Harrington’s Oceana (1656)

With the approach of the French Revolution, such works as Gabriel de Foigny’s Terre australe conue (1676) demonstrated the virtues of liberty. Francois Fénelon’s Télémaque (1699) extolled the simple life, somewhat in the spirit of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s state of nature, before private property introduced inequality and greed into human life. L’An 2440 by Louis-Sébastien Mercier (1770) anticipated the revolutionary ideas of the approaching Revolution.

Comte Claude Henri Saint-Simon’s (1760-1825) Letters from an Inhabitant of Geneva to His Contemporaries (1803) proposes that the most eminent mathematicians and scientists be given responsibility for government.

Charles Fourier's vision of Utopia is based on the absolute suppression

of individualism in favour of an all-pervasive collectivism. Fourier was

probably responsible for more Utopian projects aimed at implementing

his ideas than any other writer. See the Charles Fourier Archive.

The French Revolution

There is a strong sense in which The French Revolution was a Utopian experiment. The Decree establishing the Republican Calendar,

beginning like Pol Pot from Year Zero and dividing the day into 10

hours, 1000 minutes, 100,000 seconds etc., gives a flavour of this

utopianism. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin of Inequality Among Men and The Social Contract

(1762) provided the principles of Reason on which the constitution

could be founded. The Terror which was the outcome of such a utopian

project has been taken by many thinkers (Hegel, for example, in The Phenomenology of Spirit)

as a warning against all forms of utopianism. Similar observations have

been made about the Russian Revolution, but it would be more true to

say that Utopianism is an element of every progressive social change and every revolution.

G.A. Ellis’ New Britain (1820) and Étienne Cabet’s Voyage en Icarie (1840) expressed the vision of the experimental secular communities in the United States.

Utopia as Satire

Likewise, imaginary republics were used for the purpose of making a political point in a back-handed way. Jonathan Swift wrote Gulliver’s Travels (1726) satirising the incompetence, hypocrisy and greed of the ruling elite of his day.

Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873), a member of the ruling elite in

Victorian England and a high-ranking colonial official, wrote The Coming Race (1871) as a satirical parody on the American utopian movement. Samuel Butler (1835-1902) wrote the futuristic Erewhon

(1872) in response, satirising the injustices of Victorian England by

describing a society in which all the laws, moral prejuduces and

conceptions of science are turned into their opposite.

Full text of Edward Bulwer’s The Coming Race (1871).

Full text of Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (1872).

Socialist Utopias

News from Nowhere, tells of a society which has in some sense

reverted to an agricultural and handicraft one. The special interest of

Morris's story is that he lays out a scenario for the class struggle in

which the working class breaks from “State Socialism” and the

social-democratic conception of a “minimum program” of gradual reforms

and a “maxiumum program” consigned to an indefinite future. News from Nowhere offers a solution for attaining genuine workers democracy.

Full text of News from Nowhere, William Morris (1890).

Edward Bellamy

tells of a Rip van Winkle who wakes in the year 2000 to discover that

Socialism has been establised. Bellamy's description of socialist

society is probably the most developed expression of the

social-democratic vision of social progress. By means of the futuristic

device Bellamy does not present an isolated republic to the imagination,

but a modern industrial world which has been transformed by socialist

cooperation.

Looking Backward, 2000-1887, Edward Bellamy (1888).

In the 20th century, H.G. Wells extended the Utopian idea through the new medium of Science Fiction.

A Modern Utopia (1905) not only presents the virtues of socialism, but is a reflection on the tradition of Utopian socialism.

Full text of A Modern Utopia, H.G. Wells (1905)

Utopian writing has also been used to promote other emancipatory visions, such as feminism.

See Herland, Charlotte Perkins Stetson Gilman (1935)

Socialist Utopian Experiments

Robert Owen

(1771-1851) set about putting Utopian ideas into practice by building a

model township called New Lanark based on his own mills. Owen persuaded

a group on the way to America to abandon their journey and come to work

in his mill instead. The environs, the wages and conditions and the

education provided for the children was more than a century ahead of his

time. (New Lanark is preserved as a tourist site.)

A New View of Society, Robert Owen (1816)

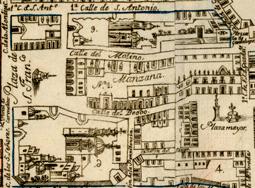

Robert Owen’s New Harmony, founded in the U.S. in 1825 was a cooperative

rather than communist society, sponsored the first kindergarten, the

first trade school, the first free library, and the first

community-supported public school in the US. Engels described Harmony

Hall in the Chartist papers in 1844:

Between 1841 and 1859, about 28 colonies were established in the United States by followers of Charles Fourier (Le nouveau monde industriel, 1829).

The Icarians, followers of Étienne Cabet,

established ill-fated communities in Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, and

California. After the American Civil War the enthusiasm for secular

utopian experiments waned.

“New Australia” was created in the 1890s, when

500 Australian socialists led by William Lane went into the Paraguayan

jungle to found a commune based on socialist principles, and their

descendants live in Paraguay to this day.

See the report of this experience by William Lane's brother, Ernest Lane: The Cosme Experience.

See the report of this experience by William Lane's brother, Ernest Lane: The Cosme Experience.

There were other such settlements in the 1890s, inspired by Laurence Gronlund’s The Cooperative Commonwealth (1884) and Bellamy’s Looking Backward, but with the rapid expansion of the Second International in late 1880s, Utopianism gave way to political, social-democratic socialism.

Utopian religious communities continue to this day, usually short-lived,

invariably centred around one powerful personality and his disciples,

declining after his death.

Twentieth Century Communes

The Great Depression

(1930-1939) put millions of workers on to the scrap heap. Many became

itinerant bums, others turned to petty crime, but many took the

opportunity to build an alternative. In Australia and other countries

where land was available, hundreds of Communes were set up, based on

Communist ideals and a subsistence economy. Despite personality clashes

between their often head-strong leaders, many were successful. The

police broke up those which could not be crushed economically, and the

onset of the Second World War brought the movement to a close.

During the 1960s and 70s, Hippy communes

(“intentional communities”) were set up in many parts of the world. The

majority of these were not serious social experiments, and most fell

victim to personality clashes or exaggerated dependence on one

individual, but some were successful and survive in good health to this day. The younger generation, educated in the “new social movements” has been brought up with sophisticated techniques for conflict resolution and consensus decision-making and work well.

Most “intentional communities” in existence today are based on variations of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s political economy, varying from little more than gated villages to LETS (Local Employment Trading Schemes) barter systems to worker-cooperatives like Mondragon.

The principal difference between these projects and communism, is that

they pre-suppose an “opting-out” from the problems of modern society,

rather than any attempt to challenge the power of multi-national

capitalism. Nevertheless, those which are successful continue to provide

a counter-example to capitalist society.

Dystopia

The opposite of “Utopia” is “Dystopia” (as in “dysfunction”).

Dystopian visions are used to issue warnings about dangers within

society or to demonstrate the absurdity of the dominant ideology of the

day by following the idea through to its “logical conclusion.”

H. G. Wells’ Time Machine

(1895) warned of the dangers of growing inequality and demonstrated the

dangers of class society by projecting class divisions forward to their

limit.

Dystopian novels appeared throughout the twentieth century. Among these are The Iron Heel (1907) by Jack London, My (1924) and We (1925) by Yevgeny Zamyatin, Brave New World (1932) by Aldous Huxley, and Nineteen Eighty-four (1949) by George Orwell. The concept of Dystopia is a frequent theme for movies such as Matrix, Mad Max, etc.

It is said people today find it easier to imagine a global disaster than

any real improvement in social conditions, let alone Utopia. So,

Dystopia is an effective ideological weapon, while the postmodern

distrust of progress makes Utopias unconvincing to most people in modern

capitalist societies. This was not always the case however, and Utopian

visions have been powerful levers for action in the past.