Precolonialism

Precolonialism

A subdiscourse of colonialism explored by postcolonial theorists.[13] Helena Norberg-Hodge has stated that, in order to do development studies, one has to first understand precolonialism.[14][clarification needed] The concept of precolonialism has also been applied to literary studies with respect to such works as Francis Bacon's New Atlantis.[15]Universalism

The conquest of vast territories brings multitudes of diverse cultures under the central control of the imperial authorities. From the time of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, this fact has been addressed by empires adopting the concept of universalism, and applying it to their imperial policies towards their subjects far from the imperial capitol. The capitol, the metropole, was the source of ostensibly enlightened policies imposed throughout the distant colonies.The empire that grew from Greek conquest, particularly by Alexander the Great, spurred the spread of Greek language, religion, science and philosophy throughout the colonies. While most Greeks considered their own culture superior to all others (the word barbarian is derived from mutterings that sounded to Greek ears like "bar-bar"), Alexander was unique in promoting a campaign to win the hearts and minds of the Persians. He adopted Persian customs of clothing and otherwise encouraged his men to go native by adopting local wives and learning their mannerisms. Of note is that he radically departed from earlier Greek attempts at colonization, characterized by the murder and enslavement of the local inhabitants and the settling of Greek citizens from the polis.

Roman universalism was characterized by cultural and religious tolerance and a focus on civil efficiency and the rule of law. Roman law was imposed on both Roman citizens and colonial subjects. Although Imperial Rome had no public education, Latin spread through its use in government and trade. Roman law prohibited local leaders to wage war between themselves, which was responsible for the 200 year long Pax Romana, at the time the longest period of peace in history. The Roman Empire was tolerant of diverse cultures and religious practises, even allowing them on a few occasions to threaten Roman authority.

Colonialism and geography

British Togoland in 1953

Anne Godlewska and Neil Smith argue that "empire was 'quintessentially a geographical project.'"[17] Historical geographical theories such as environmental determinism legitimized colonialism by positing the view that some parts of the world were underdeveloped, which created notions of skewed evolution.[16] Geographers such as Ellen Churchill Semple and Ellsworth Huntington put forward the notion that northern climates bred vigour and intelligence as opposed to those indigenous to tropical climates (See The Tropics) viz a viz a combination of environmental determinism and Social Darwinism in their approach.[18]

Political geographers also maintain that colonial behavior was reinforced by the physical mapping of the world, therefore creating a visual separation between "them" and "us". Geographers are primarily focused on the spaces of colonialism and imperialism; more specifically, the material and symbolic appropriation of space enabling colonialism.[19]:5

Maps played an extensive role in colonialism, as Bassett would put it "by providing geographical information in a convenient and standardized format, cartographers helped open West Africa to European conquest, commerce, and colonization".[20] However, because the relationship between colonialism and geography was not scientifically objective, cartography was often manipulated during the colonial era. Social norms and values had an effect on the constructing of maps. During colonialism map-makers used rhetoric in their formation of boundaries and in their art. The rhetoric favored the view of the conquering Europeans; this is evident in the fact that any map created by a non-European was instantly regarded as inaccurate. Furthermore, European cartographers were required to follow a set of rules which led to ethnocentrism; portraying one's own ethnicity in the center of the map. As Harley would put it "The steps in making a map - selection, omission, simplification, classification, the creation of hierarchies, and 'symbolization' - are all inherently rhetorical."[21]

A common practice by the European cartographers of the time was to map unexplored areas as "blank spaces". This influenced the colonial powers as it sparked competition amongst them to explore and colonize these regions. Imperialists aggressively and passionately looked forward to filling these spaces for the glory of their respective countries.[22] The Dictionary of Human Geography notes that cartography was used to empty 'undiscovered' lands of their Indigenous meaning and bring them into spatial existence via the imposition of "Western place-names and borders, [therefore] priming ‘virgin’ (putatively empty land, ‘wilderness’) for colonization (thus sexualizing colonial landscapes as domains of male penetration), reconfiguring alien space as absolute, quantifiable and separable (as property)."[23]

David Livingstone stresses "that geography has meant different things at different times and in different places" and that we should keep an open mind in regards to the relationship between geography and colonialism instead of identifying boundaries.[17] Geography as a discipline was not and is not an objective science, Painter and Jeffrey argue, rather it is based on assumptions about the physical world.[16]

Colonialism and imperialism

Marxist view of colonialism

Marxism views colonialism as a form of capitalism, enforcing exploitation and social change. Marx thought that working within the global capitalist system, colonialism is closely associated with uneven development. It is an "instrument of wholesale destruction, dependency and systematic exploitation producing distorted economies, socio-psychological disorientation, massive poverty and neocolonial dependency."[24] Colonies are constructed into modes of production. The search for raw materials and the current search for new investment opportunities is a result of inter-capitalist rivalry for capital accumulation. Lenin regarded colonialism as the root cause of imperialism, as imperialism was distinguished by monopoly capitalism via colonialism and as Lyal S. Sunga explains: "Vladimir Lenin advocated forcefully the principle of self-determination of peoples in his "Theses on the Socialist Revolution and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination" as an integral plank in the programme of socialist internationalism" and he quotes Lenin who contended that "The right of nations to self-determination implies exclusively the right to independence in the political sense, the right to free political separation from the oppressor nation. Specifically, this demand for political democracy implies complete freedom to agitate for secession and for a referendum on secession by the seceding nation."[25] Non Russian marxists within the RSFSR and later the USSR, like Sultan Galiev and Vasyl Shakhrai, meanwhile, between 1918 and 1923 and then after 1929, considered the Soviet Regime a renewed version of the Russian imperialism and colonialism.In his critique of colonialism in Africa, the Guyanese historian and political activist Walter Rodney states:

- "The decisiveness of the short period of colonialism and its negative consequences for Africa spring mainly from the fact that Africa lost power. Power is the ultimate determinant in human society, being basic to the relations within any group and between groups. It implies the ability to defend one's interests and if necessary to impose one's will by any means available.... When one society finds itself forced to relinquish power entirely to another society that in itself is a form of underdevelopment ... During the centuries of pre-colonial trade, some control over social political and economic life was retained in Africa, in spite of the disadvantageous commerce with Europeans. That little control over internal matters disappeared under colonialism. Colonialism went much further than trade. It meant a tendency towards direct appropriation by Europeans of the social institutions within Africa. Africans ceased to set indigenous cultural goals and standards, and lost full command of training young members of the society. Those were undoubtedly major steps backwards ... Colonialism was not merely a system of exploitation, but one whose essential purpose was to repatriate the profits to the so-called 'mother country'. From an African view-point, that amounted to consistent expatriation of surplus produced by African labour out of African resources. It meant the development of Europe as part of the same dialectical process in which Africa was underdeveloped."

[26][27]

According to Lenin, the new imperialism emphasized the transition of capitalism from free trade to a stage of monopoly capitalism to finance capital. He states it is, "connected with the intensification of the struggle for the partition of the world". As free trade thrives on exports of commodities, monopoly capitalism thrived on the export of capital amassed by profits from banks and industry. This, to Lenin, was the highest stage of capitalism. He goes on to state that this form of capitalism was doomed for war between the capitalists and the exploited nations with the former inevitably losing. War is stated to be the consequence of imperialism. As a continuation of this thought G.N. Uzoigwe states, "But it is now clear from more serious investigations of African history in this period that imperialism was essentially economic in its fundamental impulses." [28]

Liberalism, capitalism and colonialism

Classical liberals were generally in abstract opposition to colonialism (as opposed to colonization) and imperialism, including Adam Smith, Frédéric Bastiat, Richard Cobden, John Bright, Henry Richard, Herbert Spencer, H. R. Fox Bourne, Edward Morel, Josephine Butler, W. J. Fox and William Ewart Gladstone.[29] Their philosophies found the colonial enterprise, particularly mercantilism, in opposition to the principles of free trade and liberal policies.[30] Adam Smith wrote in Wealth of Nations that Britain should grant independence to all of its colonies and also argued that it would be economically beneficial for British people in the average, although the merchants having mercantilist privileges would lose out.[29][31]Scientific thought in colonialism, race and gender

During the colonial era, the global process of colonization served to spread and synthesize the social and political belief systems of the "mother-countries" which often included a belief in a certain natural racial superiority of the race of the mother-country. Colonialism also acted to reinforce these same racial belief systems within the "mother-countries" themselves. Usually also included within the colonial belief systems was a certain belief in the inherent superiority of male over female, however this particular belief was often pre-existing amongst the pre-colonial societies, prior to their colonization.[32][33][34]Popular political practices of the time reinforced colonial rule by legitimizing European (and/ or Japanese) male authority, and also legitimizing female and non-mother-country race inferiority through studies of Craniology, Comparative Anatomy, and Phrenology.[33][34][35] Biologists, naturalists, anthropologists, and ethnologists of the 19th century were focused on the study of colonized indigenous women, as in the case of Georges Cuvier's study of Sarah Baartman.[34] Such cases embraced a natural superiority and inferiority relationship between the races based on the observations of naturalists' from the mother-countries. European studies along these lines gave rise to the perception that African women's anatomy, and especially genitalia, resembled those of mandrills, baboons, and monkeys, thus differentiating colonized Africans from what were viewed as the features of the evolutionarily superior, and thus rightfully authoritarian, European woman.[34]

In addition to what would now be viewed as pseudo-scientific studies of race, which tended to reinforce a belief in an inherent mother-country racial superiority, a new supposedly "science-based" ideology concerning gender roles also then emerged as an adjunct to the general body of beliefs of inherent superiority of the colonial era.[33] Female inferiority across all cultures was emerging as an idea supposedly supported by craniology that led scientists to argue that the typical brain size of the female human was, on the average, slightly smaller than that of the male, thus inferring that therefore female humans must be less developed and less evolutionarily advanced than males.[33] This finding of relative cranial size difference was later simply attributed to the general typical size difference of the human male body versus that of the typical human female body.[36]

Within the former European colonies, non-Europeans and women sometimes faced invasive studies by the colonial powers in the interest of the then prevailing pro-colonial scientific ideology of the day.[34] Such seemingly flawed studies of race and gender coincided with the era of colonialism and the initial introduction of foreign cultures, appearances, and gender roles into the now gradually widening world-views of the scholars of the mother-countries.

Post-colonialism

Main articles: Post-colonialism and Postcolonial literature

Further information: Dutch Indies literature

Queen Victoria Street in the former British colony of Hong Kong

Saïd analyzed the works of Balzac, Baudelaire and Lautréamont arguing that they helped to shape a societal fantasy of European racial superiority. Writers of post-colonial fiction interact with the traditional colonial discourse, but modify or subvert it; for instance by retelling a familiar story from the perspective of an oppressed minor character in the story. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak's Can the Subaltern Speak? (1998) gave its name to Subaltern Studies.

In A Critique of Postcolonial Reason (1999), Spivak argued that major works of European metaphysics (such as those of Kant and Hegel) not only tend to exclude the subaltern from their discussions, but actively prevent non-Europeans from occupying positions as fully human subjects. Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), famous for its explicit ethnocentrism, considers Western civilization as the most accomplished of all, while Kant also had some traces of racialism in his work.

Impact of colonialism and colonization

Main article: Impact of Western European colonialism and colonisation

The Dutch Public Health Service provides medical care for the natives of the Dutch East Indies, May 1946

Economy, trade and commerce

Economic expansion has accompanied imperial expansion since ancient times.[citation needed] Greek trade networks spread throughout the Mediterranean region while Roman trade expanded with the primary goal of directing tribute from the colonized areas towards the Roman metropole. According to Strabo, by the time of emperor Augustus, up to 120 Roman ships would set sail every year from Myos Hormos in Roman Egypt to India.[41] With the development of trade routes under the Ottoman Empire,Gujari Hindus, Syrian Muslims, Jews, Armenians, Christians from south and central Europe operated trading routes that supplied Persian and Arab horses to the armies of all three empires, Mocha coffee to Delhi and Belgrade, Persian silk to India and Istanbul.[42]Aztec civilization developed into an extensive empire that, much like the Roman Empire, had the goal of exacting tribute from the conquered colonial areas. For the Aztecs, a significant tribute was the acquisition of sacrificial victims for their religious rituals.[43]

On the other hand, European colonial empires sometimes attempted to channel, restrict and impede trade involving their colonies, funneling activity through the metropole and taxing accordingly.

Despite the general trend of economic expansion, the economic performance of former European colonies varies significantly. In "Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-run Growth," economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson compare the economic influences of the European colonists on different colonies and study what could explain the huge discrepancies in previous European colonies, for example, between West African colonies like Sierra Leone and Hong Kong and Singapore.[44]

According to the paper, economic institutions are the determinant of the colonial success because they determine their financial performance and order for the distribution of resources. At the same time, these institutions are also consequences of political institutions - especially how de facto and de jure political power is allocated. To explain the different colonial cases, we thus need to look first into the political institutions that shaped the economic institutions.[44]

For example, one interesting observation is "the Reversal of Fortune" - the less developed civilizations in 1500, like North America, Australia, and New Zealand, are now much richer than those countries who used to be in the prosperous civilizations in 1500 before the colonists came, like the Mughals in India and the Incas in the Americas. One explanation offered by the paper focuses on the political institutions of the various colonies: it was less likely for European colonists to introduce economic institutions where they could benefit quickly from the extraction of resources in the area. Therefore, given a more developed civilization and denser population, European colonists would rather keep the existing economic systems than introduce an entirely new system; while in places with little to extract, European colonists would rather establish new economic institutions to protect their interests. Political institutions thus gave rise to different types of economic systems, which determined the colonial economic performance.[44]

European colonization and development also changed gendered systems of power already in place around the world. In many pre-colonialist areas, women maintained power, prestige, or authority through reproductive or agricultural control. For example, in certain parts of sub-Saharan Africa women maintained farmland in which they had usage rights. While men would make political and communal decisions for a community, the women would control the village’s food supply or their individual family’s land. This allowed women to achieve power and autonomy, even in patrilineal and patriarchal societies.[45]

Through the rise of European colonialism came a large push for development and industrialization of most economic systems. However, when working to improve productivity, Europeans focused mostly on male workers. Foreign aid arrived in the form of loans, land, credit, and tools to speed up development, but were only allocated to men. In a more European fashion, women were expected to serve on a more domestic level. The result was a technologic, economic, and class-based gender gap that widened over time.[46]

Slaves and indentured servants

Slave memorial in Zanzibar. The Sultan of Zanzibar complied with British demands that slavery be banned in Zanzibar and that all the slaves be freed.

African slavery had existed long before Europeans discovered it as an exploitable means of creating an inexpensive labour force for the colonies. Europeans brought transportation technology to the practise, bringing large numbers of African slaves to the Americas by sail. Spain and Portugal had brought African slaves to work at African colonies such as Cape Verde and the Azores, and then Latin America, by the 16th century. The British, French and Dutch joined in the slave trade in subsequent centuries. Ultimately, around 11 million Africans were taken to the Caribbean and North and South America as slaves by European colonizers.[48]

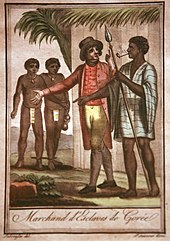

Slave traders in Gorée, Senegal, 18th century

| European empire | Colonial destination | Number of slaves imported[48] |

|---|---|---|

| Portuguese Empire | Brazil | 3,646,800 |

| British Empire | British Caribbean | 1,665,000 |

| French Empire | French Caribbean | 1,600,200 |

| Spanish Empire | Latin America | 1,552,100 |

| Dutch Empire | Dutch Caribbean | 500,000 |

| British Empire | British North America | 399,000 |

India and China were the largest source of indentured servants during the colonial era. Indentured servants from India travelled to British colonies in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, and also to French and Portuguese colonies, while Chinese servants travelled to British and Dutch colonies. Between 1830 and 1930, around 30 million indentured servants migrated from India, and 24 million returned to India. China sent more indentured servants to European colonies, and around the same proportion returned to China.[49]

Following the Scramble for Africa, an early but secondary focus for most colonial regimes was the suppression of slavery and the slave trade. By the end of the colonial period they were mostly successful in this aim, though slavery is still very active in Africa and the world at large with much the same practices of de facto servility despite legislative prohibition.[38]

Military innovation

The First Anglo-Ashanti War, 1823-31

The Spanish Empire held a major advantage over Mesoamerican warriors through the use of weapons made of stronger metal, predominantly iron, which was able to shatter the blades of axes used by the Aztec civilization and others. The European development of firearms using gunpowder cemented their military advantage over the peoples they sought to subjugate in the Americas and elsewhere.

The end of empire

Gandhi with Lord Pethwick-Lawrence, British Secretary of State for India, after a meeting on 18 April 1946

The territorial boundaries imposed by European colonizers, notably in central Africa and South Asia, defied the existing boundaries of native populations that had previously interacted little with one another. European colonizers disregarded native political and cultural animosities, imposing peace upon people under their military control. Native populations were often relocated at the will of the colonial administrators. Once independence from European control was achieved, civil war erupted in some former colonies, as native populations fought to capture territory for their own ethnic, cultural or political group. The Partition of India, a 1947 civil war that came in the aftermath of India's independence from Britain, became a conflict with 500,000 killed. Fighting erupted between Hindu, Sikh and Muslim communities as they fought for territorial dominance. Muslims fought for an independent country to be partitioned where they would not be a religious minority, resulting in the creation of Pakistan.[51]

Post-independence population movement

The annual Notting Hill Carnival in London is a celebration led by the Trinidadian and Tobagonian British community.

After WWII 300,000 Dutchmen from the Dutch East Indies, of which the majority were people of Eurasian descent called Indo Europeans, repatriated to the Netherlands. A significant number later migrated to the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.[53][54]

Global travel and migration in general developed at an increasingly brisk pace throughout the era of European colonial expansion. Citizens of the former colonies of European countries may have a privileged status in some respects with regard to immigration rights when settling in the former European imperial nation. For example, rights to dual citizenship may be generous,[55] or larger immigrant quotas may be extended to former colonies.

In some cases, the former European imperial nations continue to foster close political and economic ties with former colonies. The Commonwealth of Nations is an organization that promotes cooperation between and among Britain and its former colonies, the Commonwealth members. A similar organization exists for former colonies of France, the Francophonie; the Community of Portuguese Language Countries plays a similar role for former Portuguese colonies, and the Dutch Language Union is the equivalent for former colonies of the Netherlands.

Migration from former colonies has proven to be problematic for European countries, where the majority population may express hostility to ethnic minorities who have immigrated from former colonies. Cultural and religious conflict have often erupted in France in recent decades, between immigrants from the Maghreb countries of north Africa and the majority population of France. Nonetheless, immigration has changed the ethnic composition of France; by the 1980s, 25% of the total population of "inner Paris" and 14% of the metropolitan region were of foreign origin, mainly Algerian.[56]

Impact on health

See also: Globalization and disease, Columbian Exchange, and Impact and evaluation of colonialism and colonization

Aztecs dying of smallpox, ("The Florentine Codex" 1540–85)

Disease killed the entire native (Guanches) population of the Canary Islands in the 16th century. Half the native population of Hispaniola in 1518 was killed by smallpox. Smallpox also ravaged Mexico in the 1520s, killing 150,000 in Tenochtitlan alone, including the emperor, and Peru in the 1530s, aiding the European conquerors. Measles killed a further two million Mexican natives in the 17th century. In 1618–1619, smallpox wiped out 90% of the Massachusetts Bay Native Americans.[59] Smallpox epidemics in 1780–1782 and 1837–1838 brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the Plains Indians.[60] Some believe that the death of up to 95% of the Native American population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases.[61] Over the centuries, the Europeans had developed high degrees of immunity to these diseases, while the indigenous peoples had no time to build such immunity.[62]

Smallpox decimated the native population of Australia, killing around 50% of indigenous Australians in the early years of British colonisation.[63] It also killed many New Zealand Māori.[64] As late as 1848–49, as many as 40,000 out of 150,000 Hawaiians are estimated to have died of measles, whooping cough and influenza. Introduced diseases, notably smallpox, nearly wiped out the native population of Easter Island.[65] In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population.[66] The Ainu population decreased drastically in the 19th century, due in large part to infectious diseases brought by Japanese settlers pouring into Hokkaido.[67]

Conversely, researchers have hypothesized that a precursor to syphilis may have been carried from the New World to Europe after Columbus's voyages. The findings suggested Europeans could have carried the nonvenereal tropical bacteria home, where the organisms may have mutated into a more deadly form in the different conditions of Europe.[68] The disease was more frequently fatal than it is today; syphilis was a major killer in Europe during the Renaissance.[69] The first cholera pandemic began in Bengal, then spread across India by 1820. Ten thousand British troops and countless Indians died during this pandemic.[70] Between 1736 and 1834 only some 10% of East India Company's officers survived to take the final voyage home.[71] Waldemar Haffkine, who mainly worked in India, who developed and used vaccines against cholera and bubonic plague in the 1890s, is considered the first microbiologist.