Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment of a colony in one territory by a political power from another territory, and the subsequent maintenance, expansion, and exploitation of that colony. The term is also used to describe a set of unequal relationships between the colonial power and the colony and often between the colonists and the indigenous peoples.

The European colonial period was the era from the 16th century to the mid-20th century when several European powers established colonies in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. At first the countries followed a policy of mercantilism, designed to strengthen the home economy at the expense of rivals, so the colonies were usually allowed to trade only with the mother country. By the mid-19th century, however, the powerful British Empire gave up mercantilism and trade restrictions and introduced the principle of free trade, with few restrictions or tariffs.

Definitions

1541 founding of Santiago de Chile

The 2006 Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy "uses the term 'colonialism' to describe the process of European settlement and political control over the rest of the world, including the Americas, Australia, and parts of Africa and Asia." It discusses the distinction between colonialism and imperialism and states that "given the difficulty of consistently distinguishing between the two terms, this entry will use colonialism as a broad concept that refers to the project of European political domination from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries that ended with the national liberation movements of the 1960s."[3]

In his preface to Jürgen Osterhammel's Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview, Roger Tignor says, "For Osterhammel, the essence of colonialism is the existence of colonies, which are by definition governed differently from other territories such as protectorates or informal spheres of influence."[4] In the book, Osterhammel asks, "How can 'colonialism' be defined independently from 'colony?'"[5] He settles on a three-sentence definition:

Colonialism is a relationship between an indigenous (or forcibly imported) majority and a minority of foreign invaders. The fundamental decisions affecting the lives of the colonized people are made and implemented by the colonial rulers in pursuit of interests that are often defined in a distant metropolis. Rejecting cultural compromises with the colonized population, the colonizers are convinced of their own superiority and their ordained mandate to rule.[6]

Types of colonialism

Dutch family in Java, 1927

- Settler colonialism involves large-scale immigration, often motivated by religious, political, or economic reasons.

- Exploitation colonialism involves fewer colonists and focuses on access to resources for export, typically to the metropole. This category includes trading posts as well as larger colonies where colonists would constitute much of the political and economic administration, but would rely on indigenous resources for labour and material. Prior to the end of the slave trade and widespread abolition, when indigenous labour was unavailable, slaves were often imported to the Americas, first by the Portuguese Empire, and later by the Spanish, Dutch, French and British.

Internal colonialism is a notion of uneven structural power between areas of a state. The source of exploitation comes from within the state.

Socio-cultural evolution

As colonialism often played out in pre-populated areas, sociocultural evolution included the formation of various ethnically hybrid populations. Colonialism gave rise to culturally and ethnically mixed populations such as the mestizos of the Americas, as well as racially divided populations such as those found in French Algeria or in Southern Rhodesia. In fact, everywhere where colonial powers established a consistent and continued presence, hybrid communities existed.Notable examples in Asia include the Anglo-Burmese, Anglo-Indian, Burgher, Eurasian Singaporean, Filipino mestizo, Kristang and Macanese peoples. In the Dutch East Indies (later Indonesia) the vast majority of "Dutch" settlers were in fact Eurasians known as Indo-Europeans, formally belonging to the European legal class in the colony (see also Indos in Pre-Colonial History and Indos in Colonial History).[7][8]

The Other

"The East offering its riches to Britannia", painted by Roma Spiridone for the boardroom of the British East Asia Company.

Political geographers explain how colonial/ imperial powers (countries, groups of people etc.) "othered" places they wanted to dominate to legalize their exploitation of the land.[9] During the rise of colonialism and after; post colonialism, the Western powers perspectives of the East as the "other," different and separate from the societal norm. This viewpoint and separation of culture had divided the Eastern and Western culture creating a dominant/ subordinate dynamic, both being the "other" towards themselves.[9]

History

Main articles: History of colonialism and Chronology of colonialism

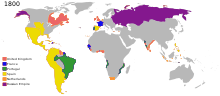

Map of colonial empires throughout the world in 1800

Map of colonial empires throughout the world in 1914

Map of colonial empires at the end of the Second World War, 1945

Modern colonialism started with the Age of Discovery. Portugal and Spain (initially the Crown of Castile) discovered new lands across the oceans and built trading posts or conquered large extensions of land. For some people, it is this building of colonies across oceans that differentiates colonialism from other types of expansionism. These new lands were divided between the Portuguese Empire and Spanish Empire (then still between Portugal and Castile - the Crown of Castile who had a dynastic union through the Catholic kings and their successors, but not of state, with the Crown of Aragon), first by the papal bull Inter caetera and then by the Treaty of Tordesillas and the Treaty of Zaragoza (1529).

This period is also associated with the Commercial Revolution. The late Middle Ages saw reforms in accountancy and banking in Italy and the eastern Mediterranean. These ideas were adopted and adapted in western Europe to the high risks and rewards associated with colonial ventures.

The 17th century saw the creation of the French colonial empire and the Dutch Empire, as well as the English overseas possessions, which later became the British Empire. It also saw the establishment of a Danish colonial empire and some Swedish overseas colonies.

The spread of colonial empires was reduced in the late 18th and early 19th centuries by the American Revolutionary War and the Latin American wars of independence. However, many new colonies were established after this time, including the German colonial empire and Belgian colonial empire. In the late 19th century, many European powers were involved in the Scramble for Africa.

The Russian Empire, Ottoman Empire and Austrian Empire existed at the same time as the above empires, but did not expand over oceans. Rather, these empires expanded through the more traditional route of conquest of neighbouring territories. There was, though, some Russian colonization of the Americas across the Bering Strait. The Empire of Japan modelled itself on European colonial empires. The United States of America gained overseas territories after the Spanish–American War for which the term "American Empire" was coined.

Map of the British Empire (as of 1910). At its height, it was the largest empire in history.

The colonial system was a major cause of World War II. The war in the Pacific was caused by Japan's efforts to create a colonial empire that sought to conquer the existing empires held by the British, French, Dutch and the United States. The war in Europe and North Africa was caused partially by Germany and Italy's efforts to create colonial empires that sought to conquer existing British, French and Russian colonial empires in these areas.

After World War II, decolonization progressed rapidly. This was caused by a number of reasons. First, the Japanese victories in the Pacific War showed Indians, Chinese, and other subject peoples that the colonial powers were not invincible. Second, many colonial powers were significantly weakened by World War II.

Dozens of independence movements and global political solidarity projects such as the Non-Aligned Movement were instrumental in the decolonization efforts of former colonies. These included significant wars of independence fought in Indonesia, Vietnam, Algeria, and Kenya. Eventually, the European powers—pressured by the United States and Soviets—resigned themselves to decolonization.

In 1962 the United Nations set up a Special Committee on Decolonization, often called the Committee of 24, to encourage this process.